In my former job, I developed seismic and acoustic data processing algorithms for various government customers. At Sandia, I ended up with a dedicated team of software engineers coding these up and delivering them as software tools for analysts. One thing I was particularly proud of were my global-search probabilistic location algorithms, which could provide formal uncertainty estimates. Finally, we could get away from ellipsoids (approximations built for speed) and provide more realistic uncertainties!

After developing algorithms, and software, and delivering these to government customers, everyone hated the non-ellipsoidal solutions. They broke all the other tools in the ‘ellipse-industrial-complex’. Everything was built around ellipses (plotting programs, database schemas, etc.)! Analysts were trained to interpret ellipses, now here were these exotic-shaped hypervolumes! The software team was asked to write code that approximated our nice non-ellipsoidal solutions with ellipses and the exotic-shaped hypervolumes were dead in the water.

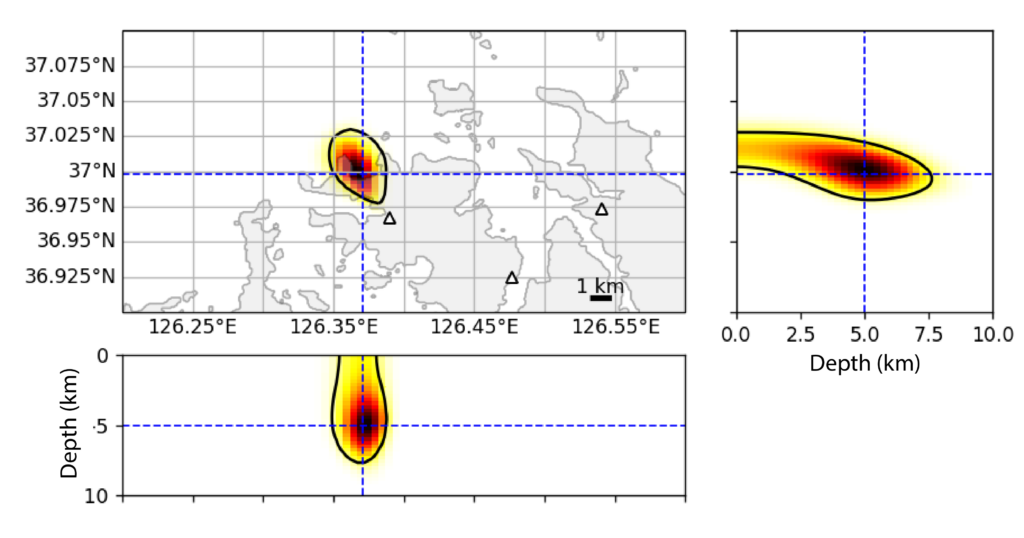

My experiences prompted me to write a short paper that describes when the true location uncertainty isn’t ellipsoidal. I’m putting the finishing touches to revisions on the paper but the basic result can be described in just a few words: you get non-ellipsoidal shapes when you have sparse observations! The figure below illustrates a typical non-ellipsoidal solution for an event at 5 km depth recorded by three seismometers.

One thing I’ve learned about writing papers so far is that they don’t always have the type of impact you expect. I’d expect nothing less with this one, but at least I will have something to point to in future in my quest to kill the ellipse.

I couldn’t agree more. One bad pick in a sparse solution 3 -5 stations could really jack things up. Typical ellipses distribute the error evenly and base the strike upon the coverage.